The last time I messaged her was May 6. Two weeks before she died. To be honest, that exchange also barely counts. The real last time was nearly a month before that. I cannot express to you how upset this truth makes me as I write it now in black and white on my screen.

It wasn’t uncommon for there to be weeks between messages. That hasn’t comforted me at all. In fact, it’s compounded the guilt. The time stamps are evidence of all the opportunities I didn’t take. The wrong choices I made, based on assumptions about a future that will never exist.

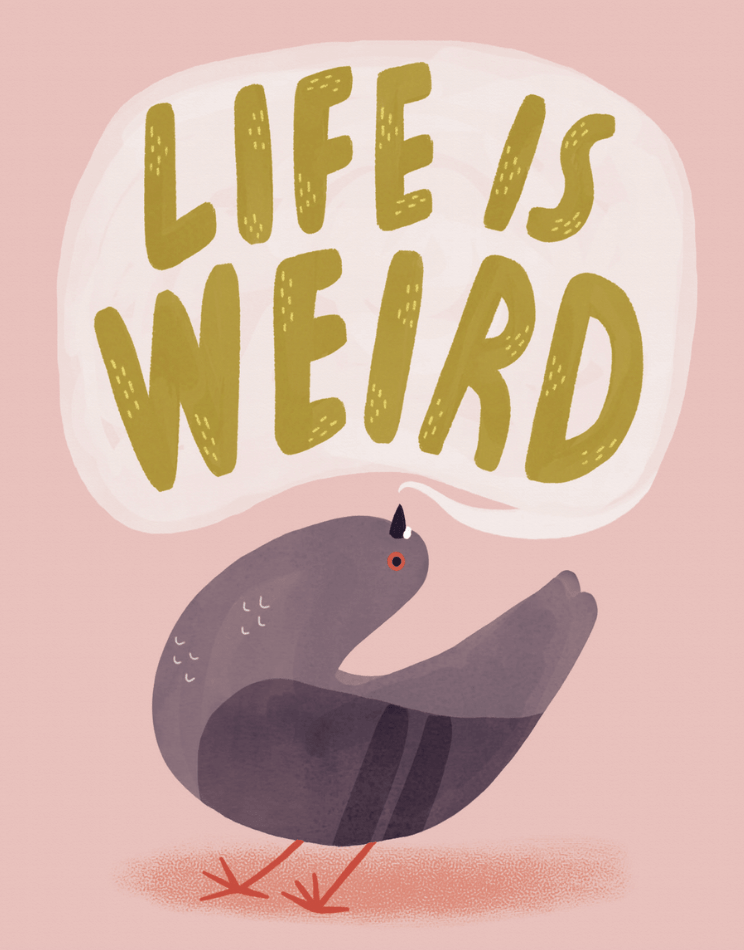

The last thing she heard from me, though, was a few days after our last text exchange. When she finally got around to opening this silly card I sent her, using an online service.

Inside was a short message:

Seeester,

I didn’t want to only have your address for the purpose of my background check, so I decided to also send you this ridiculous card.

LIFE IS WEIRD, BUT SO ARE WE. I hope you’re having a good day!

❤ Sarah

I have this card, now. It was open on the counter when I got to her home after traveling nearly 5,000 miles home. She never told me she had opened it, but I was told she had been very excited about it when it came. I hope that’s true. I wish I had written so much more in that stupid card. Is a heart emoji the same as telling someone you love them? Was a seven-word wish for a good day enough to tell her I thought about her often and wished her happiness?

The double gut punch of this all is that on May 19, the eve of my life irreparably breaking, I felt very, very content. A very important coworker and mentor was leaving, and I had written him a short letter thanking him and specifically explaining how he had impacted me. I was on good terms with a lot of people in the place I lived and worked, the place I would leave in a few short months. I distinctly remember thinking how wonderful it was to have no regrets about not saying something to someone, how pleased I was to have earnestly and generously verbalized all the things I would normally have just quietly thought before people left.

I had no idea that less than 12 hours later, I would be confronted with the unavoidable truth that I had not been as demonstrative with my sister. There had never appeared to be some transition that triggered a need to do so, I guess. As I sit here now, I think of all the hypothetical milestones I would have poured my heart out to her—a promotion, her engagement to her wonderful partner, their wedding, them buying a house. I bought into the fallacy of there being a next time, and I robbed my sister of getting to know what I thought of her, truly.

So I’ll write it now, 84 days too late.

Sister, I spoke of you often. I still try to, but the weight of what I’m trying to say right now comes from you knowing that before you were gone, I did. In a sea of people who all do the same job as me, it was refreshing to brag about you being a culinary school-trained chef. People always thought it was cool. I’m proud of you for challenging path you took and the way you excelled in every kitchen you entered. People respected you, your work ethic, and your abilities. (For the record, I also always mentioned your insane black cat, your partner, the town where you lived, your love of peanut butter cups.)

Home would never quite be home without you there. It’s why I always coordinated my trips home with you. We were a set, a pair, and I needed that precious time to overlap with you as much as possible. As I write this now, I have to grapple with the fact that home may never quite be home ever again. Thank you for all these years of bending your holiday schedule around my travel.

For our whole lives, I’ve always considered you the pretty one, and it flattered me that you liked my style. I cherished all our sister shopping dates and when you would come to me to ask for fashion advice or a second set of eyes on an outfit, especially in more recent times when that required you to message me. I would trade a whole hell of a lot for one more afternoon in the mall with you.

I am so happy you found love. I think one of the reasons I didn’t feel like we needed to talk as frequently was because I knew without any shadow of a doubt you had all the love, support, and affection you would need in your home, with your partner. You and he took care of each other in an effortlessly complementary way.

I took for granted that mom would tell me tidbits about your life, and so the time stretched long sometimes. I’m sorry. I wish I could have heard more of what I have in the past 84 days from you instead of through your friends. Your friends are lovely, by the way. I wish I could have met them with you at your favorite restaurant as a group, instead of somberly under the spectre of your loss and the vacuum you’ve left behind.

I’m proud of you. You found a way all your own and built a happy life. I wish you could have had another 60 years of time, because based on what I’ve learned since your death, you created positive ripples around you wherever you went. You left people’s lives changed for the better. I hope you knew you were a shining light for people. Somehow, I don’t think you did.

I love you.